Email: Calley@CalleyO'Neill.com

CALLEY O’NEILL’S ECOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE

DESIGN PROCESS AND INFLUENCES

INFLUENCES:

Initially, Calley’s design process was deeply influenced by the landmark book DESIGN WITH NATURE (1969) by pioneering Landscape Architect, Ian McCarg. McCarg’s book was the first treatise on ecological planning and design thinking. It delineated a process of design based on an intimate knowledge of the land, in order to create human habitats in concert with their setting, environment, and climate.

Calley was profoundly influenced by her major professor Murray Bookchin, Founder and Director of The Institute for Social Ecology, Cate Farm, Goddard College where she earned the first MA in Social Ecology. Remarkable pioneering luminaries came to teach at Cate Farm, including biologist Dr. John Todd, First Living Building Challenge Award Winner, author, Founder of The New Alchemy Institute, Ocean Arks, and originator of the Living Machine. John’s work in ecological design shaped Calley’s design in the direction of the land’s ‘original instructions’.

Calley had the opportunity to benefit from a brief intensive study with award winning organic architect/sculptor/author Christopher Day at Findhorn, Scotland and in California. Day’s design meditative approach to the land through awareness, community participation and consensus formed the foundation of Calley’s design process. Calley experienced Day’s intensives at Findhorn at the First Global Eco-Village Conference. Here is the essence of the teachings, paraphrased from Christopher Day’s writing.

‘Blending our works as seamlessly into the landscape takes conscious effort, thus we have developed a design method built upon Margaret Colquhoun's study of the four layers of landscape:

- The solid objects, physical facts, the 'bedrock' of the place.

- That which is constantly changing, flowing and growing.

- That, which lends character to a place, gives its unique 'atmosphere' and appeal.

- And that which is the essence or inner reality of a place.

- Whether it is the spirit of landscape or place, this 'four-fold' technique lends itself to group work and consensus, giving objectivity beyond the subjective.

It can be hard to get people to commit sufficient time for this process, but time is an important part of it. Knowledge matures when we "sleep on it" and ideas need time to coalesce, otherwise they are prematurely formed.

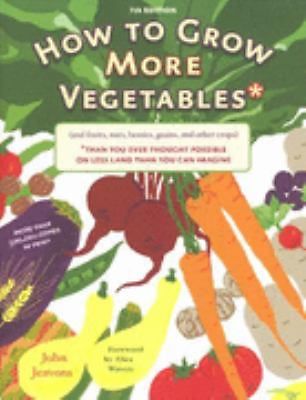

Other key influences include Calley’s agriculture teacher Charles Woodard at Goddard College and especially author/biointensive master teacher and sustainability expert John Jeavons. The great beauty of raised bed food gardens struck a natural cord in her design abilities. Other key influences include Calley’s agriculture teacher Charles Woodard at Goddard College and especially author/biointensive master teacher and sustainability expert John Jeavons. The great beauty of raised bed food gardens struck a natural cord in her design abilities.

Writings by architect Malcolm Wells deepened her fusion of art, ecology and awareness: Writing in Architectural Digest in 1971, he set forth 15 goals that he said all new buildings should strive to meet. Among them were to use and produce solar energy, to consume their own waste, to provide wildlife habitat and human habitat, and to be beautiful. (NY Times obituary, 2009)

Last, and perhaps most importantly, Calley is a highly sensitive visual being with a natural grasp of aesthetics, beauty, and design. Her visual sense is acute and aware of even the most minute details, coupled with an ability to see the big picture, the wide expanse, and the context of a landscape.

THE JOURNEY OF A CONSERVATION ARTIST AND HER

STAND FOR NATIVE HAWAIIAN LANDSCAPES

By Calley O’Neill

Destroying a tropical rainforest and other species rich ecosystems for profit

is like burning all the paintings in the Louvre to cook dinner.

Legendary Conservationist, Edward. O. Wilson

As a little girl growing up in New Jersey, I was Grampa’s gardening companion. A professional old-school photographer with an incredible green thumb, his four-tiered landscape was a magical place replete with lush Italian vegetable, herb, and flower gardens, a “humus pile”, grape vines, strawberries, and a homemade greenhouse made out of old windows. Uncle Charlie’s neighboring yard had one thing ~ a huge cherry tree. Naturally, I started growing food and making art, just like Grampa.

One day in high school, I heard some adult say the words “endangered species” and “human actions.” I was stunned. What? My trust in the goodness of humanity started to unravel. I stopped drawing humans and drew only animals—to the point that when my mom attended my UHM Campus Center mural dedication years later, she was amazed that I could paint humans. I told her I had found a people I could trust and a culture I could believe in.

When I was 21, I read How to Grow More Vegetables Than You Thought Possible* by John Jeavons, and turned our entire yard into a curving French Intensive raised bed garden. Then I read Diet for a Small Planet and became an instant vegetarian. I connected with singer/activist Harry Chapin and quit my job as an art teacher to open his first branch of World Hunger Year. I became a full-time activist determined to help eliminate hunger.

In the process of my immersion in this new world, I was introduced to Murray Bookchin, a brilliant professor with an extraordinary grasp of the history of humanity and ecology. Hearing my passion to make a difference, Murray recommended I enter his pioneering Institute for Social Ecology MA program at Goddard College. I gave away most everything I owned, packed the remnants into my Honda Civic, bid farewell to my lifelong friends, and headed to Vermont.

I went deep into social ecology, striving to understand our power as the biggest geological force on Earth, consuming the natural world that sustains us. The study of ecology was based on humans as objective observers of nature, a wildly inaccurate view. The very act of separating ourselves from nature and using it as a resource was at the core of the ecological crisis. Killing the host is a most dangerous thing to do. Murray wanted to return our populace to citizens, not consumers. We were learning how to restore wholeness through “appropriate technologies”, intensive food production, and innovative design.

The most influential pioneers of the green movement including physicist/ solar expert Amory Lovins, and ecological design innovators John and Nancy Todd, came to teach, blowing open our minds. I spent time at the Integral Urban House and New Alchemy Institute. Their agriculture/aquaculture integrated landscapes and Bioshelters were magic. This is what I was searching for: landscapes of sustenance and beauty. Life began to make sense. Later, in Hawai’i, I would understand the ancient roots of living in harmony with nature. Kumu Pua Case shared that non-productive decorative landscapes have neither meaning nor value in Hawaiian culture. ‘Aina—that which feeds… Lokahi, the harmony of the Spirit, Nature, and Humanity…

In a design intensive at Findhorn with architect Christopher Day, author of Places of the Soul, Architecture and Environmental Design as a Healing Art, I learned a whole new way of designing with nature. Ask, “What is the land calling for?” Authentic design is listening, receiving from a greater intelligence, and becoming the hands of skill for the land and the people. It doesn’t come from thinking. Einstein said nothing of value he contributed ever came from thinking. I can imagine the ‘aina calling for her children to return. I can’t imagine Hawaiian land or reefs calling for pesticides, herbicides, chemical fertilizers, mowing and blowing. One leaf blower with an inefficient two-stroke engine produces as many contaminants as a 6,000-pound SUV.

At a certain moment in time, I became aware that I could see what was—and what can be. This sudden gift of vision rocked my world. Every landscape was instantly transformed in my mind’s eye from banal to gorgeous and abundant.

Nature is the pre-eminent designer, its elegance and exuberant wild beauty towering leagues above human manicures. I could easily discern non-native and native landscapes. Native plants belong. It’s invasive messes vs. pristine elegance. I began to ‘see’ what had been been lost, and what we can do to restore health and beauty in our human-dominated landscapes. Landscape architect and author of Design with Nature, Ian McHarg pioneered ecological design and natural land planning in 1969, influencing sustainable and regenerative design development. His book had a major impact on me early on. “Follow nature’s operating instructions.” as John Todd said.

When invited to move to Oahu from Vermont in the early 80s, I jumped at the chance, and soon thereafter won the commission to paint the double-walled mural at UHM’s Campus Center, Hawai’i Ka’u Kumu. I researched and was inspired by Native Hawaiian Planters of Old Hawai’I and the highly skilled Hawaiian horticulturists of old, the Bishop Museum archives, and many oral histories. My Kumu Hulu, Braddah Frank Hewett, taught me how to design in a pono way.

I worked on many small home landscape designs, but was most inspired designing public models for integrated landscapes with native forest eco-systems, healing gardens, intensive agriculture/aquaculture, people places, and canoe gardens. Each time I presented a plan, I was told I was ahead of my time and that such landscapes weren’t possible to “maintain.” Cutting, mowing, and spraying had replaced horticulture, and there seemed no way of restoring horticulture as the key to our own survival and the health of the land.

Earl Bakken commissioned me to create a comprehensive master plan for the new North Hawai’i Community Hospital, a design acclaimed by leading landscape architects across the U. S. when I presented it at the first Therapeutic Gardens Conference in Cleveland. When Earl first brought me onboard, the front of the hospital was to be a parking lot from entry to street. While the community design charettes generated participation by over 200 people, funds and vision were limited, and only the parking lots and main elements got into the ground. Some could not fathom the value that the healing gardens would bring in fulfilling the hospital’s mission to improve the health of the citizens of North Hawai’i.

My life’s work was cut out for me in public art and ecological landscape design until… my life took another turn. I saw an elephant paint! Yes, as I watched the artist elephant Rama painting a fabulous abstract at the Oregon Zoo, I received a compelling vision of an international travelling exhibition on endangered species that would reach the hearts and minds of millions of people. After a year of writing letters, I was invited into the elephant barn and our leading-edge painting collaboration began. What you see in these paintings is the breath and power of an elephant. I worked intensively with Rama for five summers and have continued work on the paintings, research, and exhibition planning for over ten years. I was deeply honored to chosen as the featured conservation artist for the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) World Conservation Congress 2016, Hawai’I (first in the U.S.) The congress has been held every four years for 70 years as a platform for nations, NGOs, and indigenous leaders to work across boundaries to protect nature and the future. This was the first time the congress was held in the U.S. The Rama Exhibition World Premiere was a resounding success, reaching nearly 10,000 conservation leaders from 192 nations.

In 2011, I was invited to become Artist-in-Residence at Four Seasons Hualalai and continue work on a series of endangered species/ecosystems of Hawai’i and the oceanic world. This is tragically apt, for Hawai’i is the extinction and endangered species capitol of the world. Since the early 19th century, more than 90% of Hawai’i’s dryland forests have been destroyed, as have more than 50% of the mesic (environments having a moderate amount of moisture) and rain forests. UHH Department of Geography and Environmental Science Chair, botanist Dr. Jonathan Price reports that 99% of the Big Island’s dryland forest is gone. Massive deforestation has triggered tremendous losses of biodiversity, natural forest leaf mulch, and the extreme loss of topsoil. Globally, islands have lost over 67% of all biodiversity lost thus far, and are most vulnerable to climate change.

My research into endangered species often dropped me into the river of tears. Conservationists must develop an immense capacity to move forward in the face of difficult ecological knowledge, unbearable sadness, determination, and an undying optimism that we will wake up and act in time.

The interspecies paintings shown here are visual prayers created by a man, a woman, and an endangered species elephant to open our hearts so that we wake up in time and transform every possible landscape into a native and canoe plant landscape; a restoration of life that respects nature, our host culture, and future generations. Every native tree planted matters. Every native ground cover that replaces a lawn matters.

Racing extinction, we will either go down in history as the ignoramuses that ignored the human-caused sixth mass extinction event, or the noble ones who stood for the preservation of our life support system and actually made the change. Hawai’i, beloved around the world, has the extraordinary opportunity to lead the most important race of all time. And it all comes down to creating sustainable landscapes to live in.

TheRamaExhibition.org

www.CalleyONeill.com

CalleyONeill.com/LandscapeDesign.html

Art and Soul for the Earth

Big Island of Hawai'i